A version of this post appeared on my blog years ago when London wasn’t even a year old. But I just tweaked it a bit, slimmed it down , and added here and there. I think it’s better now. Here it is…

Never in my wildest dreams, as I prepared for fatherhood, did I think I was going to spend so much time with lactation nurses, reviewing the intricacies of hand expressing (including motions), analyzing breast milk volumes, discussing engorgement, and just how much breast milk one could fit in a chest freezer.

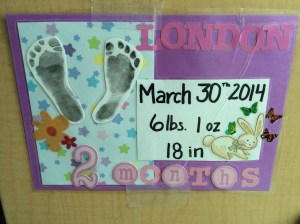

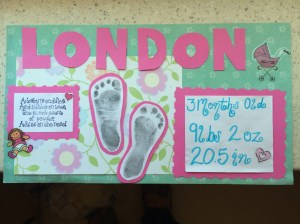

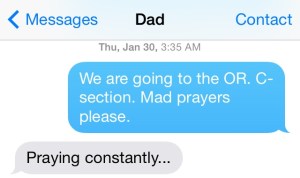

A few hours prior to my meeting with lactation consultants, thinking there were three more months to learn these things, I didn’t even know lactation nurses existed. I knew that some babies were born prematurely, but I didn’t know my wife’s breast milk would still come in just as early as our daughter wanted out at 26 weeks gestation.

So it was that our 109-day stay in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) started with a crash course in breast milk. Within those first days of life for my daughter (London), my wife (Kate) and I spoke at great length with not just one lactation nurse, but several of them about breast milk and breasts, starting with a nurse asking my wife if she was going to pump breastmilk. Partly due to the trauma of the last 24 hours, and partly due to my complete lack of knowledge about breastfeeding, I had not thought a bit about breast milk or pumping. Kate was of a similar mindset at that particular moment, but we were both satisfied to know that there was a good chance Kate’s milk would come in. The early drops of colostrum, the nutrient-dense milk first released by the mammary glands, often come in shortly after the placenta detaches from the uterine wall, no matter the gestational age.

A couple of hours later a lactation nurse wheeled into our room something that looked like a medieval torture device. They were calling it the Symphony. They hooked Kate up to it and it hummed and sucked for 18 minutes. At the end of that first session, we could just barely make out two milliliters of colostrum. A few hours later Kate produced 2.6ml and then later that night 3.8ml. The next day, January 31, marked Kate’s first 24 hours of pumping. She produced 32.6ml that day, or 1.1 ounce. The lactation team handed us a log with the direction that we were to write down when Kate pumped, for how long, and the total volume.

We then received a DVD to watch, which would apparently help Kate get more milk by hand expressing and provide tips to alleviate the pain of engorgement. We were to watch it and return it to the NICU team afterwards. That same day, we popped the DVD into my laptop to watch some before going to bed. One minute into this educational video, the biggest breast and nipple either of us had seen appeared on screen. Kate laughed so hard she began to worry she might injure herself being only two days clear of a C-section. Everything hurt. If we continued watching, we put Kate’s health at risk. I slammed the laptop shut. Tears ran down our cheeks from laughing so hard.

Who knows who is responsible for making this particular lactation video, but may I make one small suggestion on behalf of my wife and all women who have recently had C-sections? Great. Do not make the first breasts on the video also be the largest breasts known to mankind. They should not be comically large, needing 3-4 hands to get them under control. In fact, this video is a danger to new mothers everywhere, they might literally bust open their gut laughing from it, like we almost did.

Thus, it fell on me to watch the lactation video alone, gleaning from it any helpful tips and then sharing them with Kate. She was impressed. It wasn’t like Kate’s breast milk volumes needed any help. Not long after London was born, I was spending part of everyday rearranging containers of breast milk in the chest freezer in the basement—the chest freezer we needed to buy solely to store breast milk. Kate and I would joke that I knew more about hand expressing breast milk than she did so I should print up some business cards and walk around the NICU offering my services to anyone who needed them. Hand Expressions by Bryce. Simple and to the point.

By day of life 57 for our little girl, Kate was producing 1,863ml a day, or 63oz of breast milk. To put that in perspective, London was fed a total of 800ml on day 57, the most she had ever consumed in one day. In fact, it took London a long time to drink as much milk in one day as Kate got from one 20-minute pump. A point was reached where no amount of rearranging the breast milk in the freezer would make room for more. I picked up a second chest freezer at Costco and Kate started to fill that, too.

For the months London was in the NICU we rented a Symphony pump, which at the time retailed for $1500-2500, and kept it in our bedroom. We started to call it the pump house. When at home, Kate disappeared every three to four hours to spend some quality time with the Symphony. As all moms know that schedule wreaks havoc on sleep and work responsibilities, but Kate did an excellent job. I did what I could by waking with her every time throughout the night, assisting in bottling of the milk, labeling and recording volumes, washing pump parts, and then delivering milk to the freezers in the basement. So, at our house, at least two times a night, Netflix and chill was swapped out for Netflix and pump.

As Kate tapered off the pump, we were just filling up the second chest freezer and the lactation nurses understood why Kate was putting an end to pumping. She had developed a reputation in the NICU as a super producer. At London’s discharge, on May 19th, 109 days after she was born, the NICU staff wrote messages to us. One of our favorites from the lactation team wrote, “Your mom was a rock star with pumping. She could have fed three babies in the NICU!”

Next week, London will be six-months-old and I can thaw breast milk from three months back. And right now it’s lunch time for the little girl, to the chest freezer I go.